About

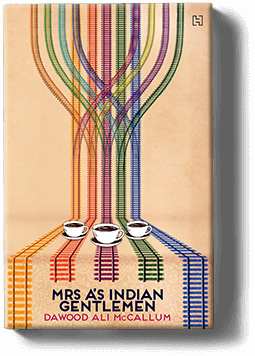

It’s 1943, and war rages across Europe. In Britain, the Great Western Railway Works’ labour force is comprised of a few men too valuable, old or infirm for active service and thousands of recently recruited women. With critical skills in short supply, the British government looks to the Empire to provide vital expertise in the run -up to the D Day invasion.

And that is how railway engineer Imtiaz ‘Billy’ Khan, logistics supremo Vincent Rosario and maths prodigy Akaash Ray find themselves in Swindon, lodging with the well-intentioned Mrs A, hilariously navigating bland food, faulty toilet cisterns, secret assignments and a mutual distrust of one another.

This is a rollicking tale of misadventure about what happens when cultures collide, dedicated with affection to the town of Swindon.

‘Everything is good about Swindon but sometimes I don’t think the people of Swindon realise how good it is. I want everyone to be proud of Swindon and say, “Hey, this is a good place. We’re proud to be from Swindon.”’

Lord Joel Joffee 1932-2017

Extract

Akaash was first down to breakfast as the 6.30 hooter sounded, followed shortly after by Vincent in a grey three-piece suit and a blue tie. Akaash, head buried in a book propped up against the sugar bowl, wore the clothes he had arrived in.

The table was prepared for three. ‘You’re not eating with us, Mrs Atkinson ?’ Vincent asked.

‘I’ve already had mine,’ she said, although Vincent doubted that was true. She was full of apologies about the paucity of the meal on the table – a pot of tea, three slices of bread, a tiny cube of butter and watery strawberry jam. She assured them that now she had their ration cards she’d be able to do much better. In fact, as soon as she’d seen them off and washed up, she assured them both, she’d be off to the shops to stock up – particularly with vegetables, she concluded with an ignored smile to Akaash.

‘Mrs Atkinson,’ Vincent began carefully. ‘There are only the two bedrooms upstairs. I was just wondering where you…’

‘Don’t you worry your head about me,’ she said, brushing his question aside. ‘I make myself very comfortable. Snug as a bug in a rug. I only hope you all slept as soundly as I did.’

She poured out tea and as she leaned over Vincent’s shoulder she confided in a quiet voice that, if he fancied it, she had dripping. Having no idea what she was talking about, he thanked her and declined.

‘Well, let Mr Khan know,’ she whispered.

‘I will,’ Vincent assured her, thinking that there were few things he was less likely to do.

‘Did you hear the birds singing first thing this morning?’ he asked Akaash.

‘Above Khan’s snoring? No.’

Vincent crossed his legs and leaned back, holding his cup and saucer on his lap. ‘I think I might borrow a book about British birds from the Institute.’

Akaash gave a brief head wobble to acknowledge he’d heard.

‘Funny how they sing so beautifully when they’re such drab and dull-looking little things.’

Akaash sighed. ‘You always this chatty in the morning? You’re a one-man dawn chorus yourself.’

‘I just think we got off on the wrong foot yesterday. What I said about your qualifications. And your… protest. I’m sorry.’

‘Forget it.’

Vincent checked his watch. ‘Where is Khan? We don’t want to arrive late.’

‘Getting dressed,’ said Akaash, still not looking up. ‘Said he wanted me out of the room before he got out of bed. Who’d have thought a big, ugly brute like him would be so prissy?’

‘Any idea where they’re putting you?’ asked Vincent. ‘I’m not asking you to give away any secrets. Just wondered.’

‘Something to do with signalling is all I was told. Logistics. Movements. Communications. Want me to head up some new area.’

‘Movements! That’s my area too. Maybe we’ll be working together.’

‘Or you maybe you’ll be working for me.’

At that moment, Billy burst into the kitchen just as Sally was putting a replenished pot of tea on the table. To say he made an entrance would be an understatement. He was resplendent in lustrously polished knee-high boots, white jodhpurs and a hip-length woollen jacket with a wrap-over front, mandarin collar, and silver buttons bearing the Scindia crest. In his left hand he carried the hat box that had accompanied them from Southampton.

‘Oh! Doesn’t he look wonderful?’ Sally sighed and promptly took out an old bedsheet to offer him as a giant napkin.

‘No. He looks like an idiot,’ Vincent said.

‘Wait till I put my pagri on,’ said Billy, waving away the sheet and opening the hat box. Carefully, as though he was handling a sacred relic, he lifted out a pre-tied, heavily starched deep blue turban. ‘Then you’ll get the full effect.’

Akaash finally looked up. ‘I am not walking into the Works with him dressed like that. He looks like a…’

‘I’ve already said that,’ said Vincent.

‘Up to you. I’m presenting a letter from His Highness and my credentials from the Durbar so I’m wearing uniform.’

‘You have a uniform?’

‘For formal occasions, of course. This is it.’

‘I thought you were an engineer.’

‘I am.’

‘You look like a doorman at some posh brothel.’

‘You’d know, would you?’

‘Look,’ said Vincent, ‘Much as I hate to agree with Comrade Stalin over there, I think he might have a point.’

‘Why?’ asked Billy huffily. ‘Whatever happened to all that stuff about respecting our culture?’

Akaash shook his head and with an eloquent sigh returned to his reading.

‘Well, think about it,’ said Vincent. ‘Today’s not likely to be easy for any of us, is it? There’s bound to be some, I don’t know, resentment? Three foreigners marching in and telling these people how to do their jobs? Who likes that?’

Akaash gave a mirthless chuckle.

‘I’m sorry, but I just don’t see it,’ said Billy, stubbornly. ‘They invited us to come here to help them. We’re all in this together. Standing shoulder to shoulder against a common foe, and all that. Why should there be any… difficulties?’

‘You really don’t get it, do you?’ said Akaash.

‘No, I don’t. Anyway, even if there is, putting on a bit of a show will help.’

‘Impress the natives, you mean?’

‘If you want to put it that way, yes.’

‘You sure you’re not British?’

Billy frowned. ‘You two are the British. I’m from Gwalior.’

Akaash closed his book and opened his mouth to speak but Vincent threw up a hand. ‘Don’t! Don’t even start!’ He turned to Billy. ‘I just think we don’t want to draw too much attention to ourselves.’

‘I think attention is going to be drawn no matter what,’ Billy pointed out. ‘We’re three – well, two and a half – Indians walking through a town that hasn’t seen a foreigner since they hanged a monkey a hundred and fifty years ago thinking it was Napoleon.’

‘Did that really happen?’ asked Akaash, fascinated. ‘Here in Swindon?’

‘I don’t know. It happened somewhere. Probably. I’m trying to make a point here.’

‘You’re determined to go dressed like that?’ asked Vincent.

‘Absolutely,’ said Billy. ‘And actually, if we’re talking about who wears what, I think he’s the one who needs to change,’ he added, jerking his head towards Akaash.

‘These are the English clothes I was issued with in Bombay. And I’m not spending good money on any more.’

‘All finished?’ asked Sally, coming in from the scullery, drying her hands on her apron. ‘Lovely to hear the three of you sounding so much at home. Chattering away in your own lingo.’

The three of them looked at each other, confused.

‘We were speaking English.’

‘Oh.’

***

By the time they arrived at the Works to the sound of the 7.20 hooter, Billy was starting to think he might indeed have made a bit of a mistake. Throughout their short walk along the terraced streets of Swindon, as increasing numbers of men and women joined the flow of humanity heading toward the main gate, he attracted ever more cheers, jeers and wolf whistles. He was too stubborn to admit his error and in any case there was no time to go back to Ashton St and change. So he held his head high and acknowledged the greetings with as much dignity as he could summon. He shook hands with a few smirking well-wishers, patted the head of a small boy who stood transfixed and gaping, and returned the exaggerated salute of the watchman at the gate who threw his right hand up to his temple, palm out, stamping his right foot to the ground to much applause.

The catcalls continued into the Works and it was a relief to get to the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s office, where Billy’s appearance was met by little more than raised eyebrows, averted eyes and poorly hidden grins. They waited around a smiling Miss Jenning in the outer office for Hartshorne to finish what seemed – from what they could hear through the closed doors – to be a difficult conversation. Billy, determined not to crease his uniform, declined the offered chair, and as the other two sat down he tugged his jacket straight, adjusted his pugri and cleared his throat. All three were more nervous than they cared to admit, and each was determined to show it as little as possible.

Hartshorne emerged from his office, closing the door quickly behind him, but not quickly enough for them to miss the shout of, ‘Over my dead body…’

‘That would be too much to hope for,’ he muttered to a sympathetic Miss Jennings, who indicated the three waiting men with a tilt of her head.

‘Goodness!’ said Hartshorne, looking Billy up and down as the other two stood. ‘Right. All paperwork properly completed? Welcome to the Great Western Railway! I was going to introduce you to your new colleagues all at the same time but on second thoughts, I think we’ll focus on Mr Rosario’s role first. That’s the one everyone seems to be getting most steamed up about. Miss Jennings? Can we rustle up some tea for our new employees? Mr Rosario, I’ll be back for you in five minutes. Mr Khan… oh, never mind,’ he said, returning to his office.

‘Wonder what that’s all about,’ said Akaash, looking around the room. As the secretary had headed off to brew some tea, he took the opportunity to glance through the correspondence in her in-tray.

‘I have a pretty good idea,’ said Vincent. ‘Do you really think you should be rummaging through Mr Hartshorne’s mail?’

‘Information is power,’ said Akaash, unperturbed.

Vincent glanced over his shoulder at the document he was perusing. ‘I’m sure the estimate for laundry costs for next month will be a huge help to the drive for home rule,’ he sneered. They both quickly stepped back from the desk as Billy gave a warning cough on seeing the handle on Hartshorne’s door turn.

Vincent was called in.

‘Good luck,’ said Billy, offering Vincent his hand.

Vincent glanced down, paused, then shook hands with him. As he withdrew his hand, he held it up and was pleased to see not a tremor of nerves. ‘Thanks,’ he said, ‘but luck will have nothing to do with it.’